The work of Architect Isaac G.Perry The only Armory in the state currently in use for residential purposes.

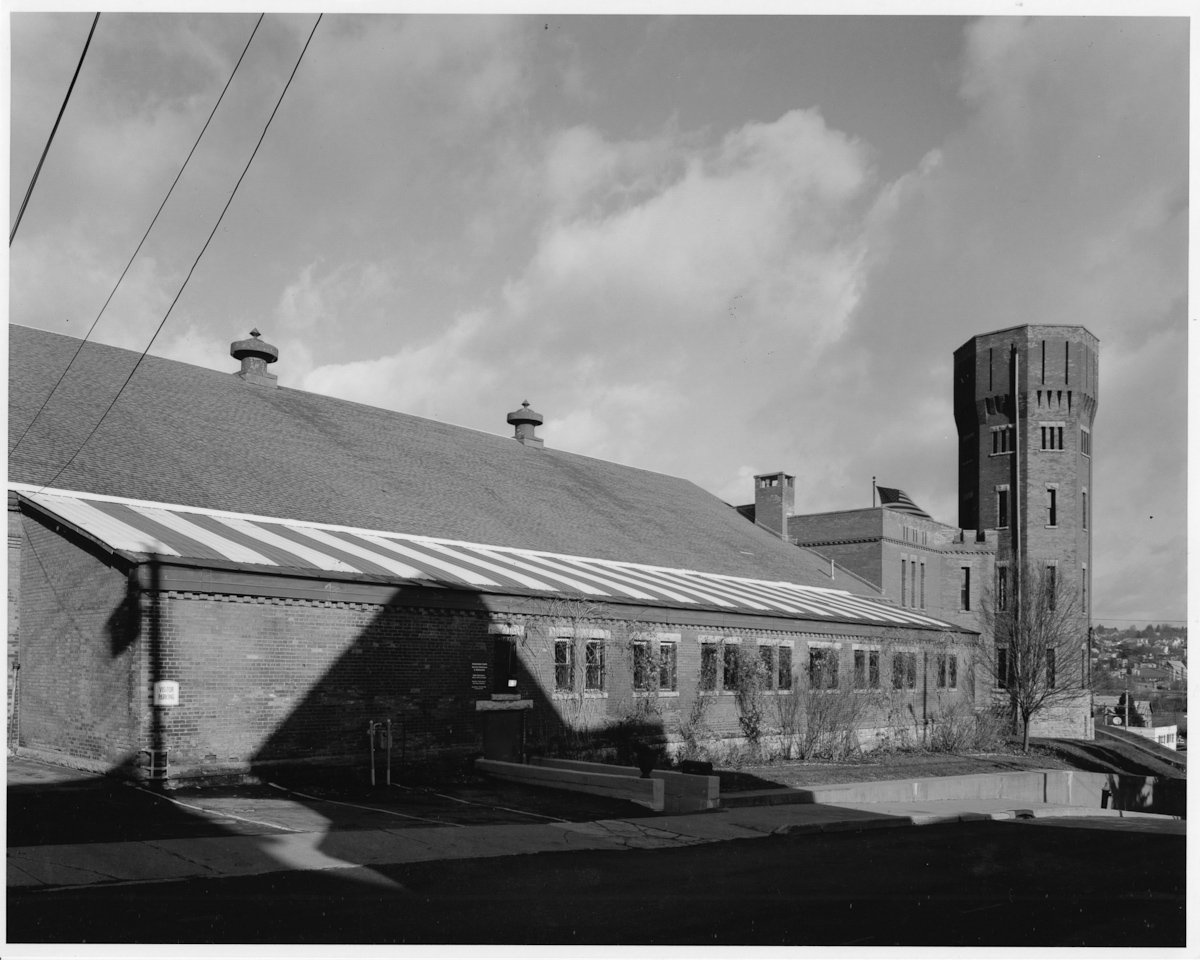

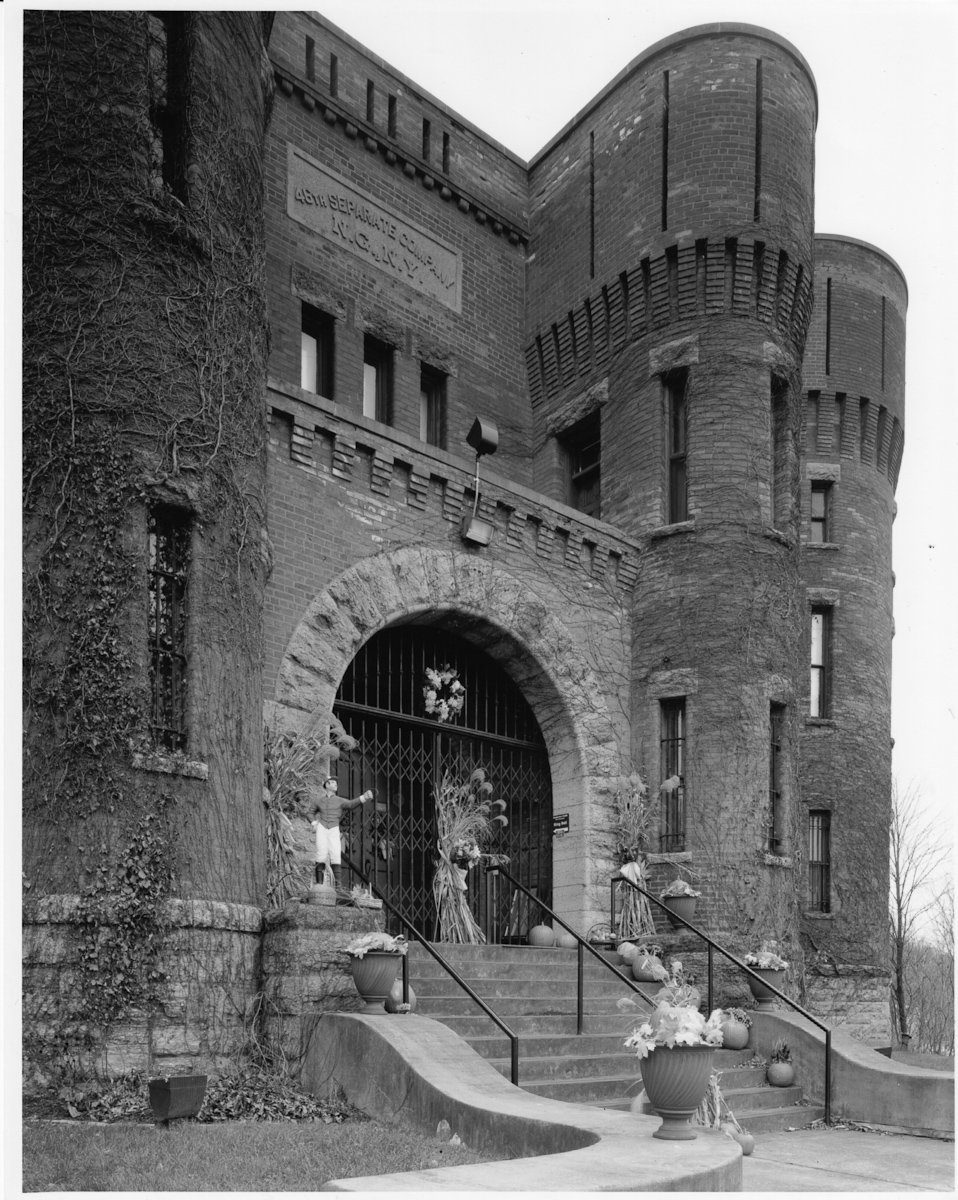

Amsterdam Armory—Historic and Architectural Overview - Photos and text by Bruce G. Harvey, Historian Built in 1895, the former National Guard Armory in Amsterdam was one of dozens that were built throughout New York State in the few decades surrounding the turn of the 20th century. While each had a distinct design, they all shared a “family resemblance.” The Armory, now in private hands as a residence and B&B, is called the “Amsterdam Castle”—an apt name since the family residence of New York’s historic armories was based quite deliberately on medieval imagery. Architectural styles in 19th century America were used deliberately by architects and builders to create images and to convey meanings and associations in the minds of those who lived and worked in the buildings or just passed by them on the street. It is left to the historians and observers of later ages to work back from the styles to understand the periods in which the styles were popular. The medieval-inspired National Guard armories in New York give us historians plenty to work with, and help everyone to understand the various architectural details in and on the Amsterdam Castle. It is important to start with the simple fact: these Armories were built by the State of New York for individual National Guard companies in each community. For those who are not aware, the National Guard is the successor to the independent, community-based militias of the Revolutionary War era and the early decades of the United States. Citizens in the new American nation were justifiably wary of a powerful, national, standing Army; such centralization of military power, as they had seen from European history, represented a threat to the liberty of free citizens. Instead, the nation relied on local militias that could be called up and organized under the small Regular Army in times of need. There were few such times of need through the middle of the 19th century, and the funding of militias tended to be haphazard. Their facilities for meeting and training, which the local communities provided, were informal and generally shared with other community functions such as markets and courthouses. The Civil War, however, placed a great burden on the militias throughout the nation, and pointed to the need for more formal attention. In 1863, during the depths of the war, Congress passed the Armory Act in which all state militia units became part of the National Guard; the Act also required each state to supply their National Guard units with arms and equipment. In the period of confusion after the Civil War, however, when the nation’s strife was more political than military, the states again slipped into lassitude with regard to the National Guard. Later in the 19th century, however, the nation began to witness a period of great civic unrest as the combination of rapid industrialization and extensive immigration, all taking place within the suddenly growing cities, made this formally rural nation very nervous indeed. Beginning in the late 1870s, industrial workers began to organize into unions of various stripes, many of which lobbied for improved conditions in pay and faced various sorts of resistance; many of these strikes and counter-strikes turned violent and required military intervention both to restore peace and, occasionally, to try to force workers back to work. With threats of violence in communities both great and small, and yet without a sizeable national standing Army, the nation increasingly turned to its National Guard units to keep the peace at home. Suddenly, the Armory Act of 1863 seemed to make a lot more sense, with New York leading the way in the design and construction of new armories. It is important to remember that Amsterdam, along with much of the Mohawk River Valley, was a heavily industrialized region which attracted vast numbers of Eastern European immigrants, making the fear of labor unrest and violence seem all the more plausible. Uncertainty about the effects of industrialization, which was a part of the drive to construct new National Guard armories, also influenced the choice of architectural style for the new facilities. As a part of the language of styles which the architects used, references to historical periods were designed to evoke certain feelings and associations based on commonly-held historical understandings, making particular styles appropriate for particular uses. The Gothic Revival, and other variants derived from medieval sources, pushed any number of buttons in the mid and late 19th century in America. Americans in the early years of the Republic drew almost exclusively on classical styles for both public and private architecture. Classical styles pointed back to those alleged paragons of democracy and republicanism, ancient Greece and Rome, from which many Americans saw the new nation having descended. At the same time, America came into being during the self-proclaimed Age of Reason, and classical styles, with their formal rules of order and geometry, seemed most appropriate. Early in the 19th century, however, cracks in the order appeared as many of the nation’s cultural leaders worried about the over-reliance on abstract reason and the loss of emotion and faith; a part of this was a concern for the new industrial order, which put formerly personal relations onto a more machine-like basis. As one historian has noted, the Gothic Revival “met a real social need for some antidote to the Classical Revival’s over-insistence on geometry, reason, order, balance, symmetry, precision.” In its early uses by pioneering architects and designers, the Gothic Revival often was called the Castellated style, as it relied for some of its effects on having castellations, or notched parapets at the top of the building like the medieval castles of old. More generically, however, the Gothic Revival included three key components: an emphasis on verticality, such as in the use of pointed arches rather than the rounded arches of the classical revival; the use of asymmetrical forms and components; and the more vivid combination of textures and patterns to attract the eye. All of these can be seen in the later National Guard armories in New York. As a residential style, the Gothic Revival was largely out of fashion by the time of the Civil War. By that time, however, it had morphed into a variety of Picturesque styles that drew roughly from medieval sources, and referred to a wide range of cultural associations that had a great appeal to Americans in the mid and late 19th century who were anxious over their place in history and the world. These medieval-inspired Picturesque styles found continued use largely in various institutional uses. Churches, for example, liked the various Gothic and medieval styles for calling to mind the Christian culture of the middle ages, while universities and libraries liked the references to the images of monks and scholars in medieval libraries and universities. The popular association of the medieval period with knights and castles made the new impulse toward Armories a natural fit. The prototype for all National Guard Armories in New York was the Seventh Regiment Armory in New York City. Constructed in 1879, it had all of the key components of later armories around the state: its design was inspired by medieval and Gothic military architecture and was intended to inspire awe, fear, strength, and patriotism; it functioned both as a military facility for training and storage and as a clubhouse for its members; and it consisted of an administration building in the front and a drill shed attached to the rear. Amsterdam’s Armory was designed in 1895 by Isaac Perry, who served as the de facto State Architect from the late 1880s until his retirement in 1899. He designed as many as 40 National Guard armories for small towns and large cities throughout the state, all of them based on the Seventh Regiment Armory prototype. As with his other armories, the Amsterdam Armory was massive in scale and constructed of brick, resting upon a rough stone foundation. The front Administration section features an asymmetrical north-facing façade with an engaged five-story octagonal turret at the northeast corner and a lower three-story engaged rounded turret at the northwest corner, with two lower two-story rounded turrets flanking the off-center entrance. The entrance between the turrets consists of a round-arched sally port, framed in rough-hewn limestone and protected by a metal portcullis or gate, with the insignia of the 46th Separate Company carved in stone on the second floor above the entrance. In keeping with the medieval castle theme, the windows across the façade are narrow, vertical rectangular openings, with rough-hewn limestone sills at the bottom and lintels across the top. The façade is imposing in its own right with the massive turrets and sally port entrance. The visual impact is greatly increased, however, by the building’s location on its site, a tall bluff overlooking the Mohawk River and the City of Amsterdam. The drill shed extends from the rear (south) of the Administration section, opening directly from the rear of the entrance foyer. It features a gable roof with the steel truss framing visible from the interior. The interior of the drill shed is primarily a large, unarticulated space; it now houses a full-size basketball court. An intriguing feature of the drill shed is the full-width balcony that opens from the second floor staircase landing of the Administration building. The balcony is protected by a railing consisting of beautifully turned wooden spindles. The east side of the building features a lower one-story section that runs the length of the drill shed, and contains spaces for locker and store rooms. The west of the building, meanwhile, is covered by a garage wing that was added in the 1950s; the garage features a flat roof supported by closely-spaced metal trusses. Given this range of medieval-inspired details, the former National Guard Armory clearly lives up to its new name of the “Amsterdam Castle.” Its architectural details are clearly worth a closer look in the following photographs. Click here to learn more about Historian Bruce Harvey

1.

2.

Next to the massive corner turrets, the most recognizable medieval feature of the Amsterdam Armory is the entrance. The key element is the round-arched sally port; in defensive terms (appropriate to a castle), the sally port is a secured, controlled entranceway, usually including two successive doors. In the case of the Amsterdam Armory, the outer door is a metal grille, similar to a portcullis which, in medieval castles, were opened by raising it vertically along tracks in the side walls. The sally port here is framed by rough hewn limestone voussoirs; with the grated portcullis, it protects an open entryway before the heavy wooden front door. The entryway is one story in height, and forms a balcony on the second floor; the balcony in turn is framed on each side by projecting oval-shaped turrets with richly detailed corbels. Above the balcony, a stone plaque identifies the Armory as the home of the 46th Separate Company of the NY National Guard; in 1898, the 46th Separate Company became “G” Company of the 105th Infantry Regiment of the NY National Guard.

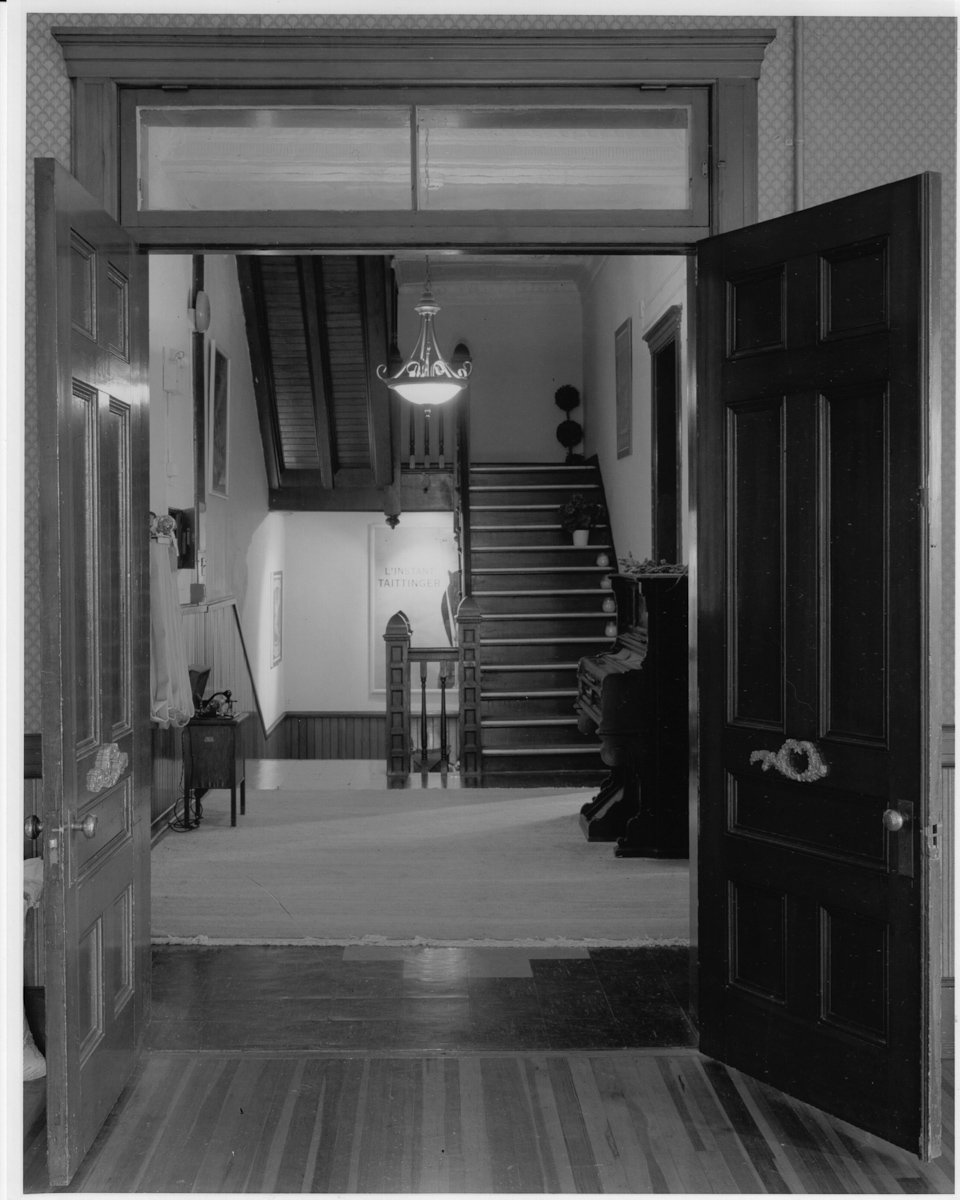

Once admitted through the portcullis and the heavy front door, visitors come into the central foyer of the Administration Section of the Armory. This is a public space, with doors leading left and right into either private or administrative rooms, and is wide enough to hold many people. The door at the rear of the foyer, directly opposite the front door, serves as an entrance through a short hallway into the massive drill shed at the rear of the building, while a staircase at the rear of the foyer to the right provides access to the second floor. The terrazzo floor likely is not the original floor, as suggested by the placement of “Co. G/105th Inf.” in the immediate foreground; the original occupant, the 46th Separate Company, became G Company of the 105th Infantry Regiment only in 1898, three years after the Armory was built.

In keeping with the defensive theme of a medieval castle, the interior parts of the Amsterdam Armory were not meant to be inviting. The foyer clearly limits access to the interior rooms, which are secured with heavy wooden doors. Unlike many houses of the Victorian period, the staircase which provides access to the second floor rooms is not a prominent architectural feature meant to be seen and admired by visitors and serving as a continuation of the foyer. Instead, the staircase is hidden from view behind the front rooms, forcing visitors and residents to make a 90-degree turn. In keeping with the building’s institutional use, it is also a common staircase that provides access to the basement as well as the second floor. Although planned as a utilitarian staircase, it was designed with modest wooden embellishments including a coffered newel post, elegant wainscot paneling, and drop pendants and paneling beneath the flight rising from the intermediate landing to the second floor.

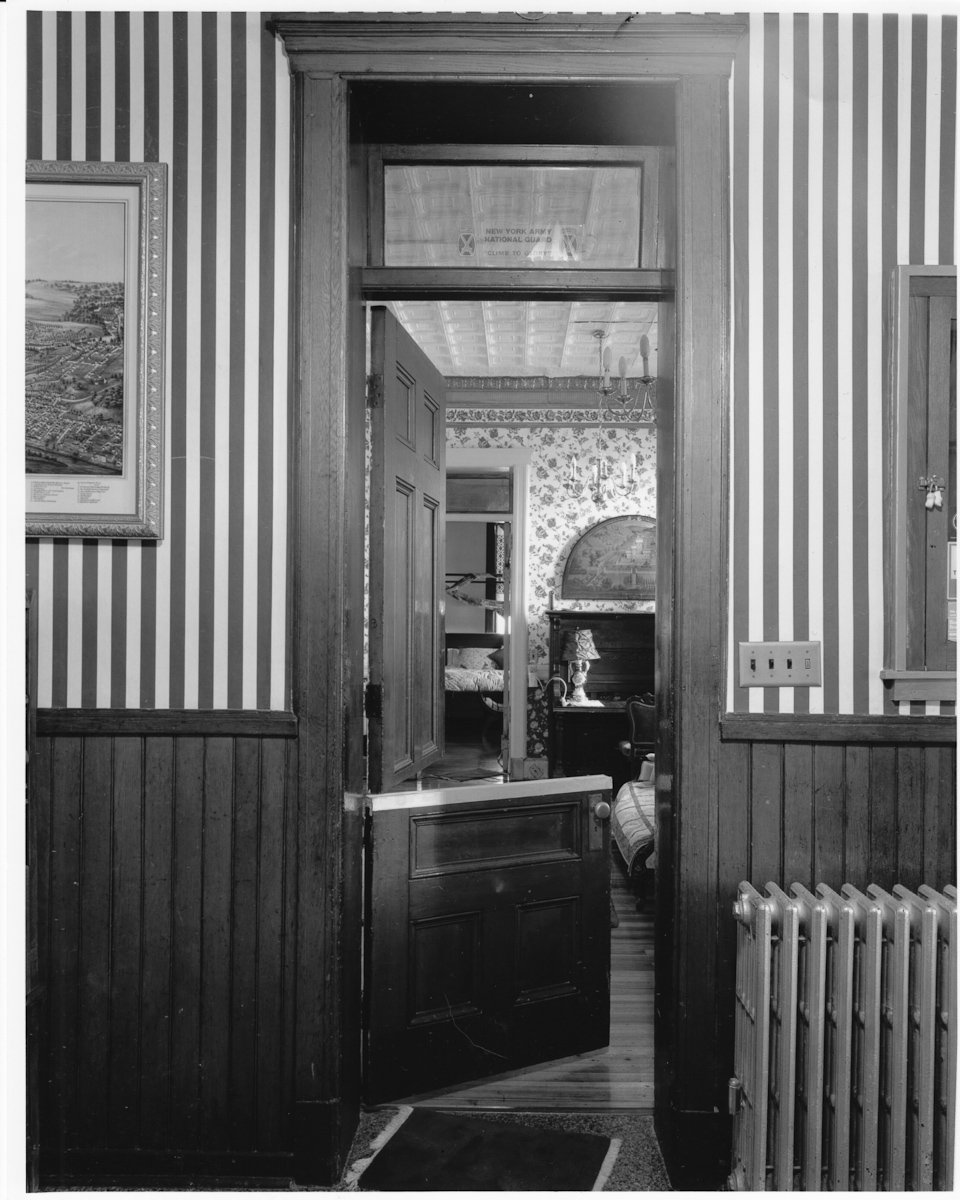

The first door to the right upon entering the foyer from the front door now opens to a guest suite with three rooms—a sitting room and bedroom in enfilade, with a bathroom opening from the bedroom. Originally, however, the enfilade suite served in part as a pantry through which goods could be dispersed. As a result, the entrance to the suite is protected by a Dutch door in which the top portion can be opened while locking the bottom portion. Although built in 1895, during the High Victorian period in America, the architectural embellishments in the Armory are modest, with a simple wooden door surround with a transom, and a simple yet elegant wainscot. Looking closely, however, one can see the ceiling of the first room in the suite, which is clad in ornamental pressed metal.

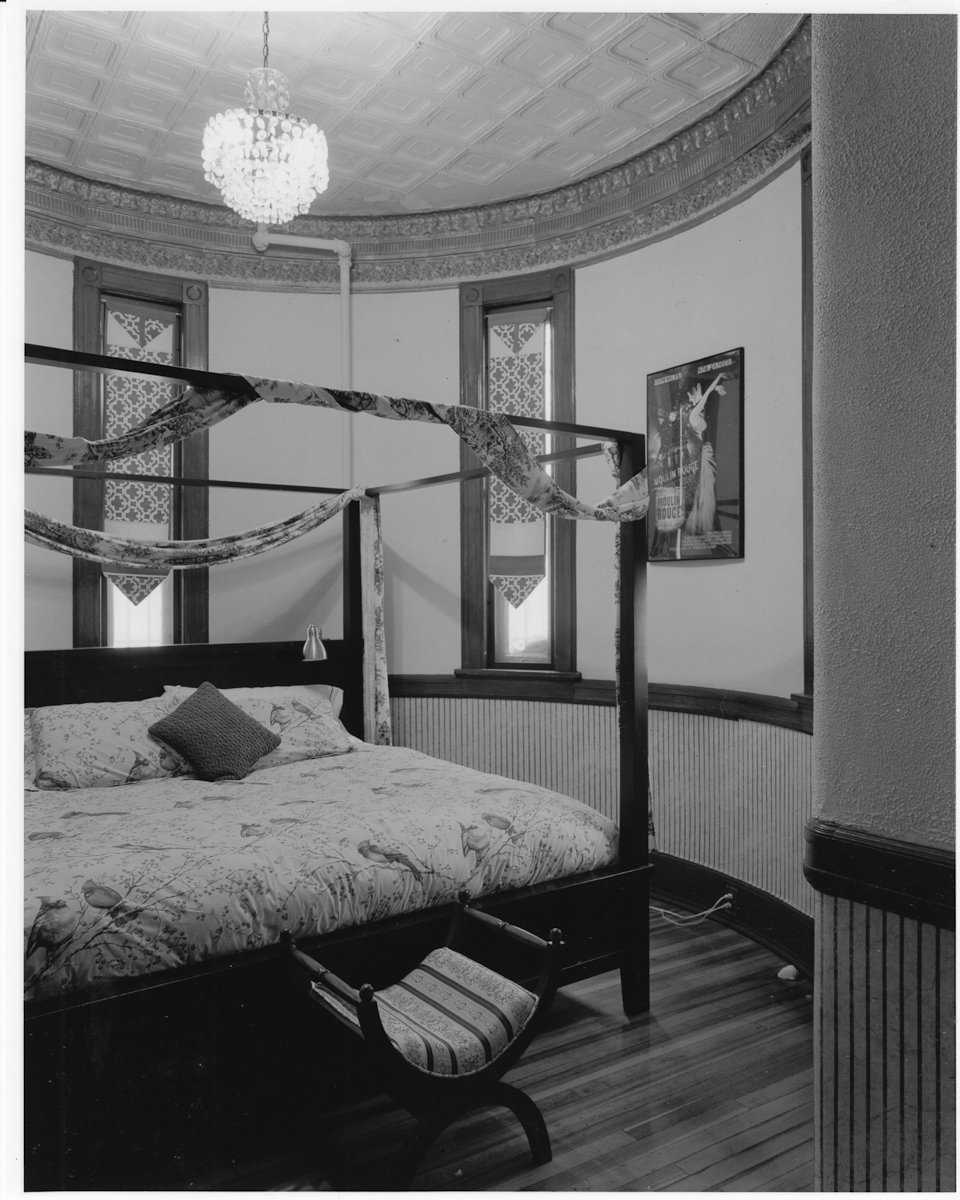

The second room in the suite at the front of the Armory is now used as a bedroom for a guest suite. This room is located in the projecting turret at the northwest corner of the house, and the elegant cornice betrays the curved shape of the turret. The curved shape of the room’s walls is reinforced by the paneled wainscot, while the narrow windows that help to create the image of a medieval castle on the exterior feature Italianate frames on the interior, marked by the circular rosettes at the top corners. The ornamental qualities of the room are then enhanced by the ornamental pressed metal ceiling.

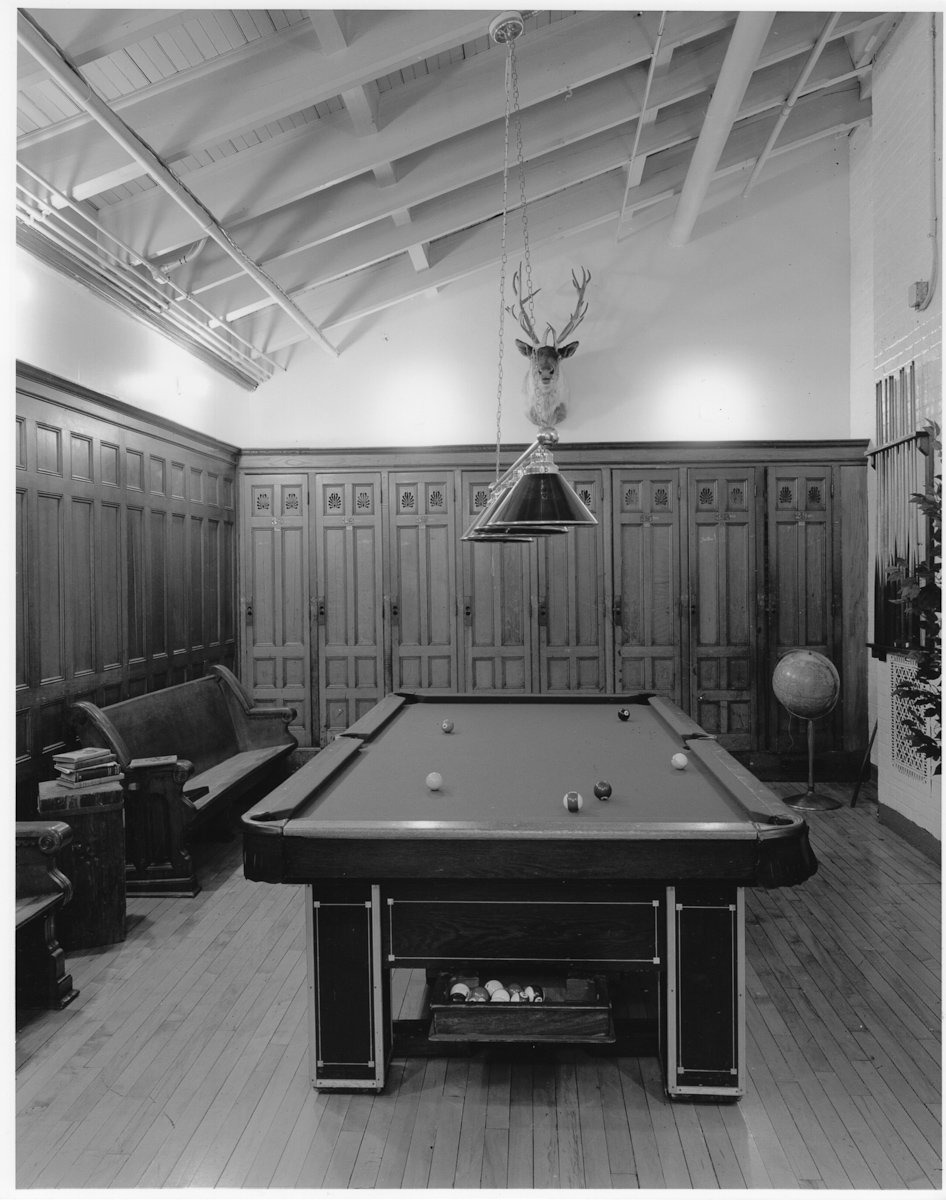

The central foyer, seen in the photograph above, also provides access to the drill shed at the rear of the building. A short hallway connects the drill shed to the front Administration section. A billiard room now opens from the hallway, making for a pleasant recreation space separate from the residential portions of the restored Armory. The connective purpose of the room can be seen in the sloping roof which links the administrative and exercise sections of the Armory.

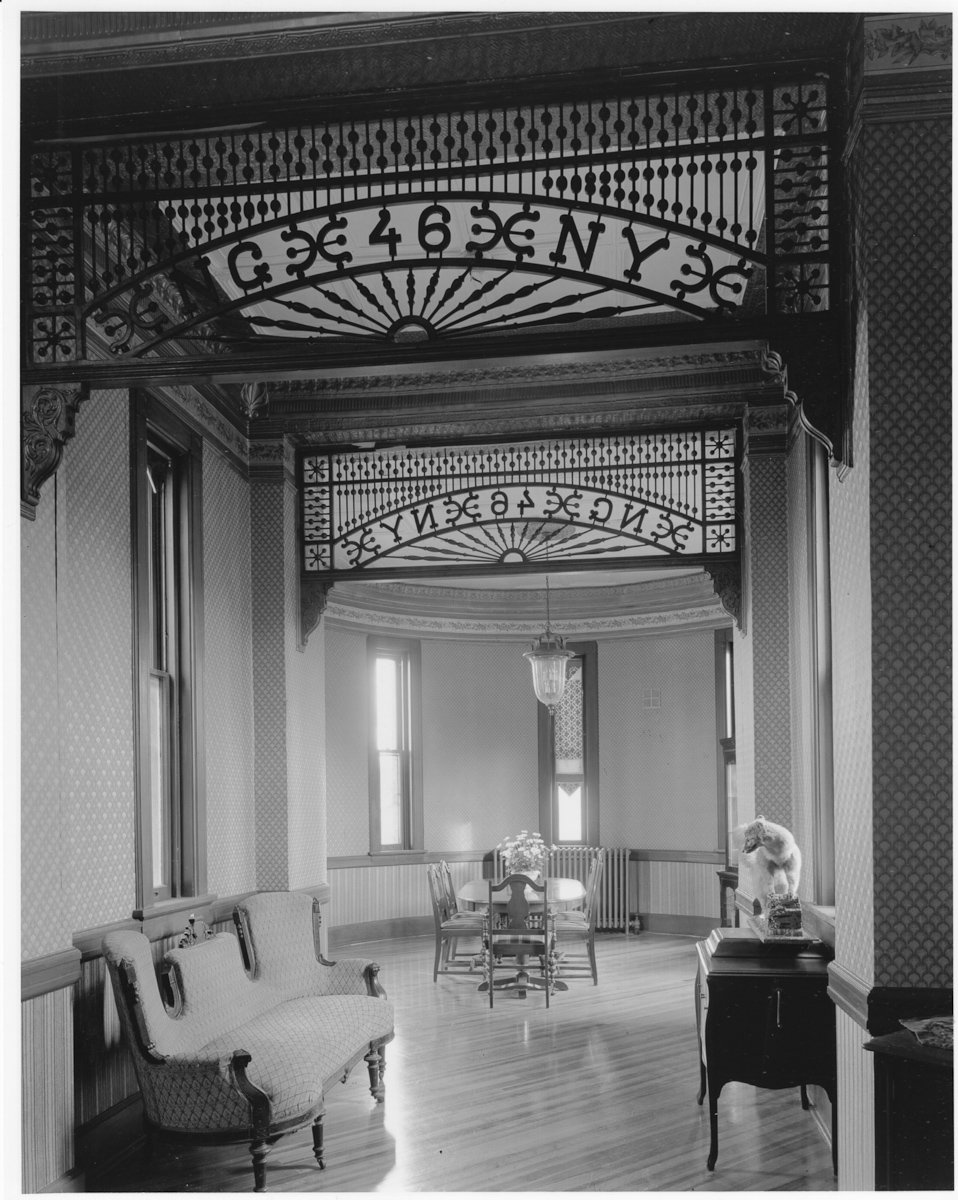

Once on the second floor, the eastern portion of the building contains a large open meeting room that opens directly from the staircase landing. This open meeting room in turn leads, by way of a short archway, to a reading room in the tall, five-story turret at the northeast corner of the building. The curved cornice line of the reading room, which is just visible in the background of the photograph, indicates its placement within the turret. The most distinctive features of the archway, however, are the spindle friezes at each end in which “NG 46 NY” is spelled out, indicating the building’s use originally by the 46th Separate Company of the NY National Guard. In 1898, this Company became “G” Company of the105th Infantry Regiment of the NY National Guard.

The large open meeting room on the east side of the second floor opens directly from the staircase landing. As discussed above in relation to the foyer, the staircase is not a public feature of the building and is set to the back and to one side. The second floor landing, therefore, opens to a short hallway that has no direct access to natural light. In compensation, though, all of the doors that open onto the landing have transoms at the tops; included within the simple classical-styled door frames, the transoms allow the natural light from the rooms that face the front into the staircase landing. The short hallway itself, meanwhile, is generous in its proportions, and the staircase on this second floor still retains the simple but elegant wooden details including a coffered newel post and paneling and a drop pendant on the underside of the flight leading to the third floor.

The short hallway on the second floor has a generous size in part to allow it to serve as an anteroom to the Commander’s Office. Despite the overwhelmingly medieval feeling of the Armory’s exterior, this room features a very handsome wooden fireplace surround which was designed with distinctly classical revival elements including the columns resting on double plinths, compressed acanthus capitals, and an elegant entablature consisting of an architrave with egg and dart molding, a curved convex frieze, and a cornice consisting of three bands of molding. The firebox is surrounding decorative glazed bricks beneath a projecting mantle supported by curved brackets, while a mirror with beveled edges is set between the mantle and the entablature. The status of the space, which now serves as one of the B&B guest rooms, is indicated on the door by the sign indicating that the room is for “Officers Only.”

This view shows the drill shed, looking toward the front Administration section. The drill shed, which extends from the rear of the Administration section, features a gable roof with the steel truss framing visible from the interior. The short hallway from the front Administration section is visible in the center of the photograph. The interior of the drill shed is primarily a large, unarticulated space, and provided indoor space for the National Guard troops to train and drill. An intriguing feature of the drill shed is the full-width balcony that opens from the second floor hallway of the Administration building. The balcony is protected by a railing consisting of turned wooden spindles. The drill shed now houses a full-sized basketball court.

This is a detail view of the metal trusses that support the drill shed roof. It was taken from the balcony, and is looking toward the rear of the building. The construction details of the trusses are clearly visible in this view, and show how the use of steel revolutionized the practice of architecture in the late 19th century. Steel retains a great deal of strength even with it is thin, which allows for openness in the space that it contains. The individual thin steel bars are joined by gromets, and make for a very rigid yet lightweight structural system for this large roof. An intriguing feature of the drill shed which is visible in this view are the radiator heating pipes which line the rear wall of the building, forming L-shapes as they surround the rear entrances.

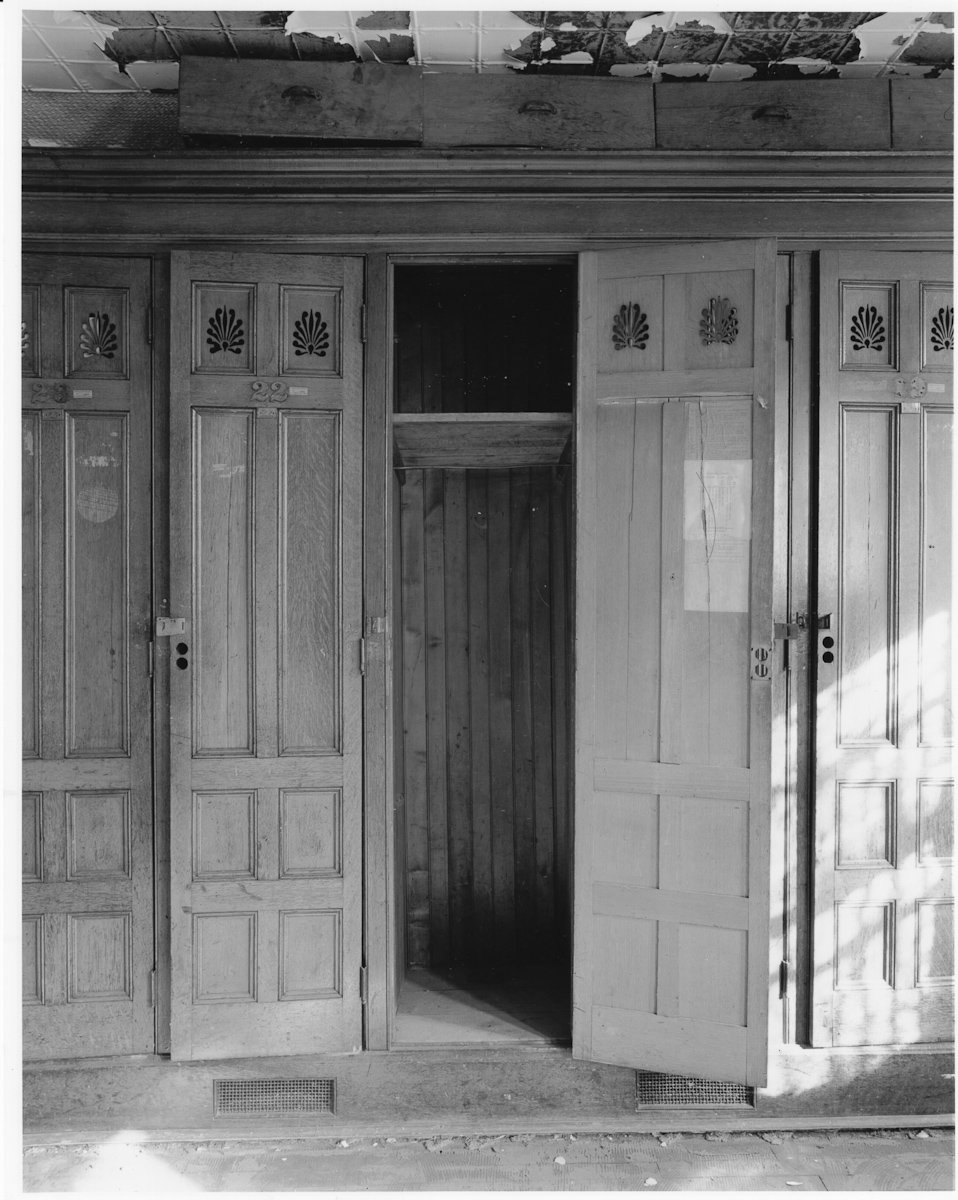

The Amsterdam Armory, like all National Guard armories in New York State, were designed not as residential spaces, but as spaces for both administrative and training functions. In a sense, they were very large clubhouses for the members of the National Guard company, to which the members would come for training and exercise. An essential part of the drill shed, therefore, was the locker room. This is a large, unarticulated space that lines the east wall of the drill shed beneath its own roof, with individual lockers in oak with doors featuring eight recessed panels; the top panels contained decorative piercings which allowed for air circulation. Although nearly all of the armory has been restored in recent years, the locker room has not, and retains much of its original, turn-of-the-century feel. An important part of that historic character is formed by the original instructions to the troops, which were printed on papers that were then posted on the inside doors of the lockers. Many of these original instructions remain, as shown in this view.

Much of the Amsterdam Armory remains in its original condition, even if restored. In the 1950s, however, the State added a garage to the west side of the building. The original outside wall of the Armory’s west side is visible in this photograph, with the vertical buttresses along the wall and original window openings now replaced with modern brick. The roof is a distinctive feature of this garage, as is clear in this view. The lightweight steel trusses are very closely spaced, providing vastly more stability than is necessary for the flat metal roof above; clearly over-engineered, the roof is capable of supporting a helicopter, should it be necessary.

Not all of the spaces in the Armory were glamorous, as this photo attests. Located beneath the locker room section along the east side of the drill shed, this space shows the original stone foundation on the right side. The galvanized ductwork, however, is a modern addition.

The Amsterdam Armory remains heated as it originally was, by means of steam radiators. While the armory contains a vast amount of space, the building’s solid masonry walls provide a high degree of natural insulation. Despite this, the building still requires a significant amount of power to keep sufficient steam coursing through the building’s veins of pipes and radiators; at the time that the building was constructed, the ability to provide steam heat throughout such a large building was seen as innovative and a very useful modern convenience. The twin boilers in the basement provide witness to the planning that went into keeping the rooms throughout the Armory comfortable. |